Accurate weighing is the foundation of science. A Laboratory Balance is a precision instrument, not just a tool. If your starting data is flawed, everything fails.

Calibration is risk management. It ensures traceability. While a routine check confirms daily function, calibration identifies specific deviations in your Laboratory Balance.

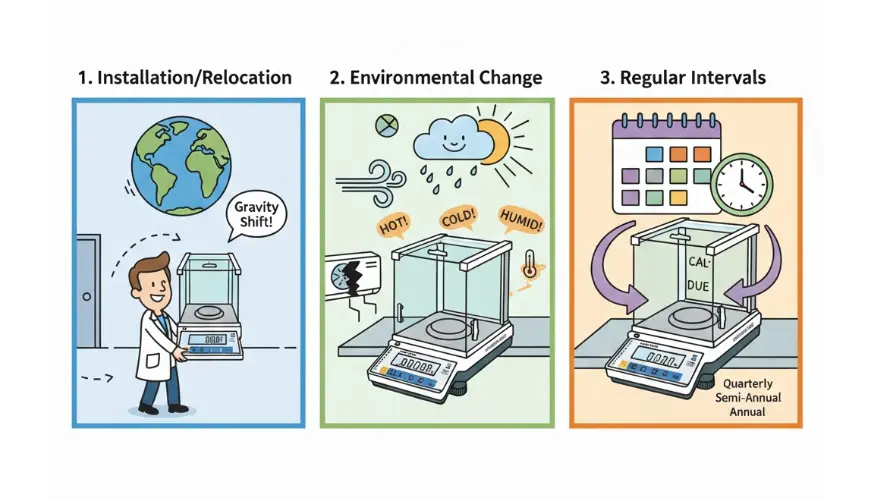

I. 5 Critical Triggers for Calibration

Timing is everything. While many labs follow a set schedule, certain events demand an immediate calibration to maintain integrity.

1. After Initial Installation or Relocation

Never assume a new balance is ready out of the box. Gravitational acceleration varies across the globe. Moving a balance from one room to another, or even across a hallway, changes the environmental forces acting on it. Always recalibrate after any physical move.

2. Significant Environmental Changes

Precision instruments are sensitive. Fluctuations in laboratory temperature, humidity, or atmospheric pressure can expand or contract internal components. This is especially true for microbalances. If your HVAC system fails or the seasons change, it’s time to check your accuracy.

3. Regular Time Intervals

Consistency builds trust. Depending on your risk level, you should establish a fixed cycle. Whether this is quarterly, semi-annually, or annually, a scheduled calibration ensures that long-term electronic drift is accounted for.

4. After Major Maintenance or Repair

If a technician replaces an internal sensor or performs a deep clean, the balance’s baseline has changed. Performance must be re-evaluated immediately. Never resume critical weighing tasks until a post-repair calibration is documented.

5. Deviations During Routine Checks

Your daily tests are your first line of defense. If you use a standard weight and the result exceeds your preset tolerance range, stop immediately. This deviation is a red flag that a formal calibration is required to find the root cause.

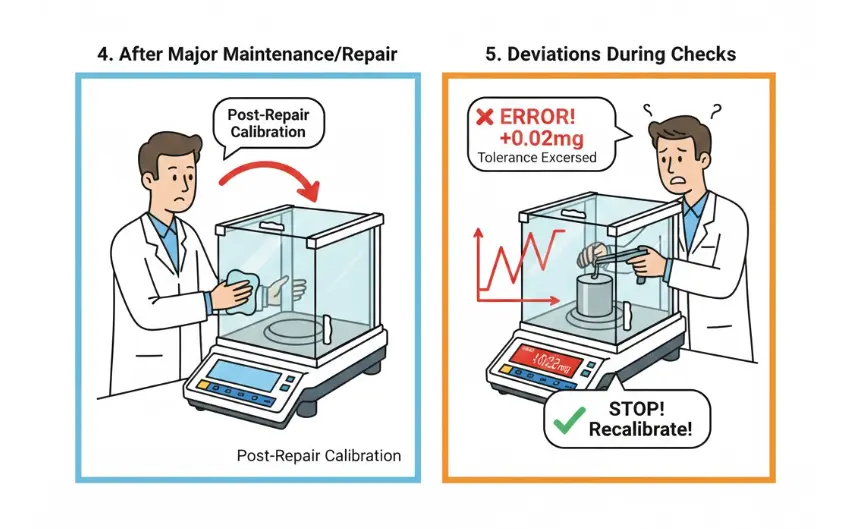

II. Determining Calibration Frequency via Risk Assessment

How often is “often enough”? The answer depends on your specific risk matrix.

- Criticality of the Process: Does this measurement affect patient safety or final product quality? Higher stakes require higher frequency.

- Frequency of Use: A balance running 24/7 undergoes mechanical stress. It needs more attention than a unit used once a week.

- Tolerance Range: If your SOP requires $\pm 0.01\text{mg}$ accuracy, your margin for error is tiny. Frequent calibration is your safety net.

- Historical Stability Data: Review your logs. If your balance has been rock-steady for two years, you might safely extend the interval. If it drifts often, shorten it.

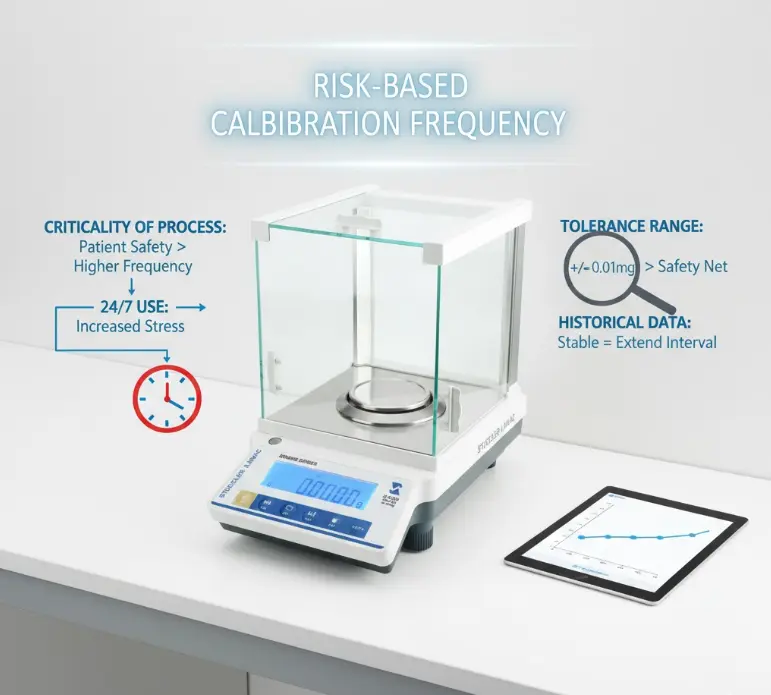

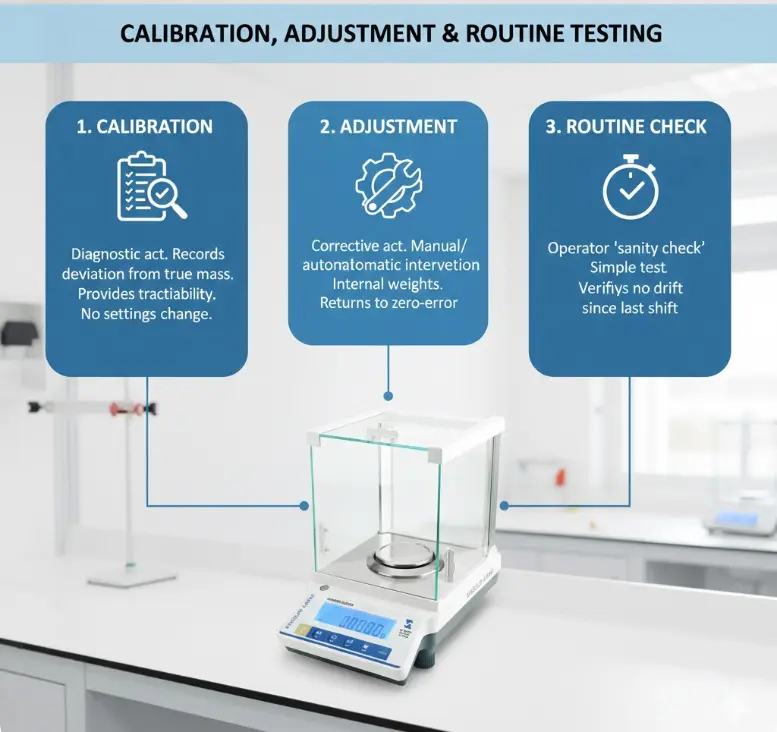

III. Calibration, Adjustment, and Routine Testing

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they serve different roles in a compliant lab.

- Calibration: This is a diagnostic act. It records the deviation between the displayed value and the true mass. It provides traceability but does not necessarily change the balance’s internal settings.

- Adjustment: This is a corrective act. It involves manual or automatic intervention (like internal motorized weights) to bring the balance back to a zero-error state.

- Routine Check: Think of this as a “sanity check.” It’s a simple test performed by the operator to ensure the device hasn’t drifted since the last shift.

IV. Industry Compliance & Standards

For those in regulated industries, “best practice” is “required practice.”

- USP <41> and <1251>: In the pharmaceutical sector, these standards define strict weighing accuracy and repeatability requirements. They mandate that balances be calibrated over their entire operating range.

- ISO 17025: This is the gold standard for testing and calibration laboratories. It ensures that your calibration results are traceable to international standards.

- Audit Preparation: Auditors look for a “paper trail.” Always keep your Calibration Certificates organized. They prove your equipment was compliant at the time of use.

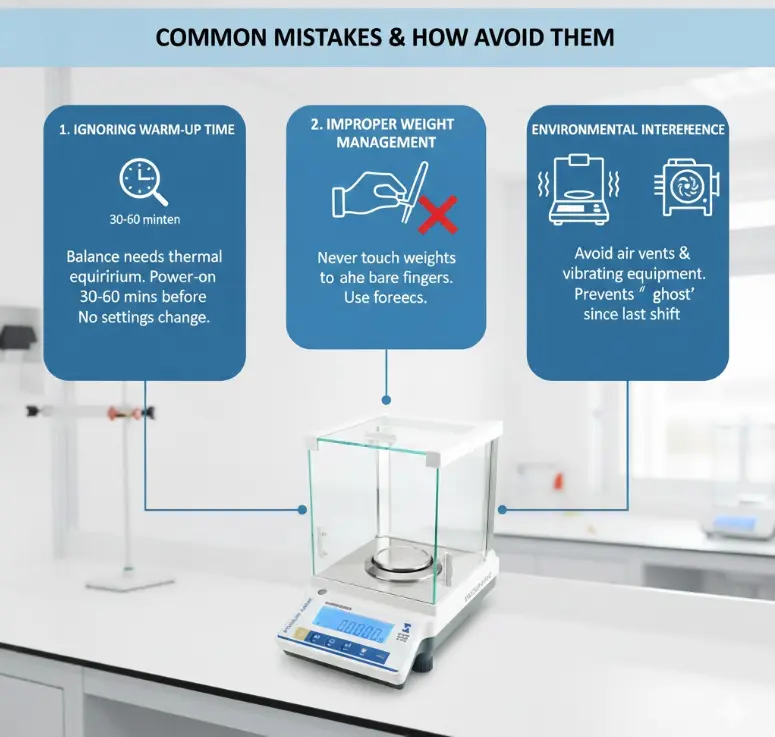

V. Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Even the best equipment fails if handled poorly. Here are three common pitfalls:

1. Ignoring Warm-Up Time

Electronic balances need to reach thermal equilibrium. Most require 30 to 60 minutes of power-on time before they are stable enough for calibration.

2. Improper Weight Management

Never touch standard weights with bare fingers. The oils from your skin add mass. Always use specialized forceps or gloves.

3. Environmental Interference

Is your balance near an air vent? Does the table vibrate when the centrifuge runs? These external factors can create “ghost” readings that ruin a calibration.

Summary

The most successful laboratories move away from “reactive correction.” Instead, they embrace proactive prevention. By establishing a clear calibration calendar and following a strict SOP, you protect your data and your reputation.

Accuracy starts with the right equipment. If you are looking to upgrade your laboratory’s precision, explore the high-performance range at Stuccler. Our Laboratory Balances are engineered to meet the most demanding compliance standards, ensuring your measurements are correct every single time.